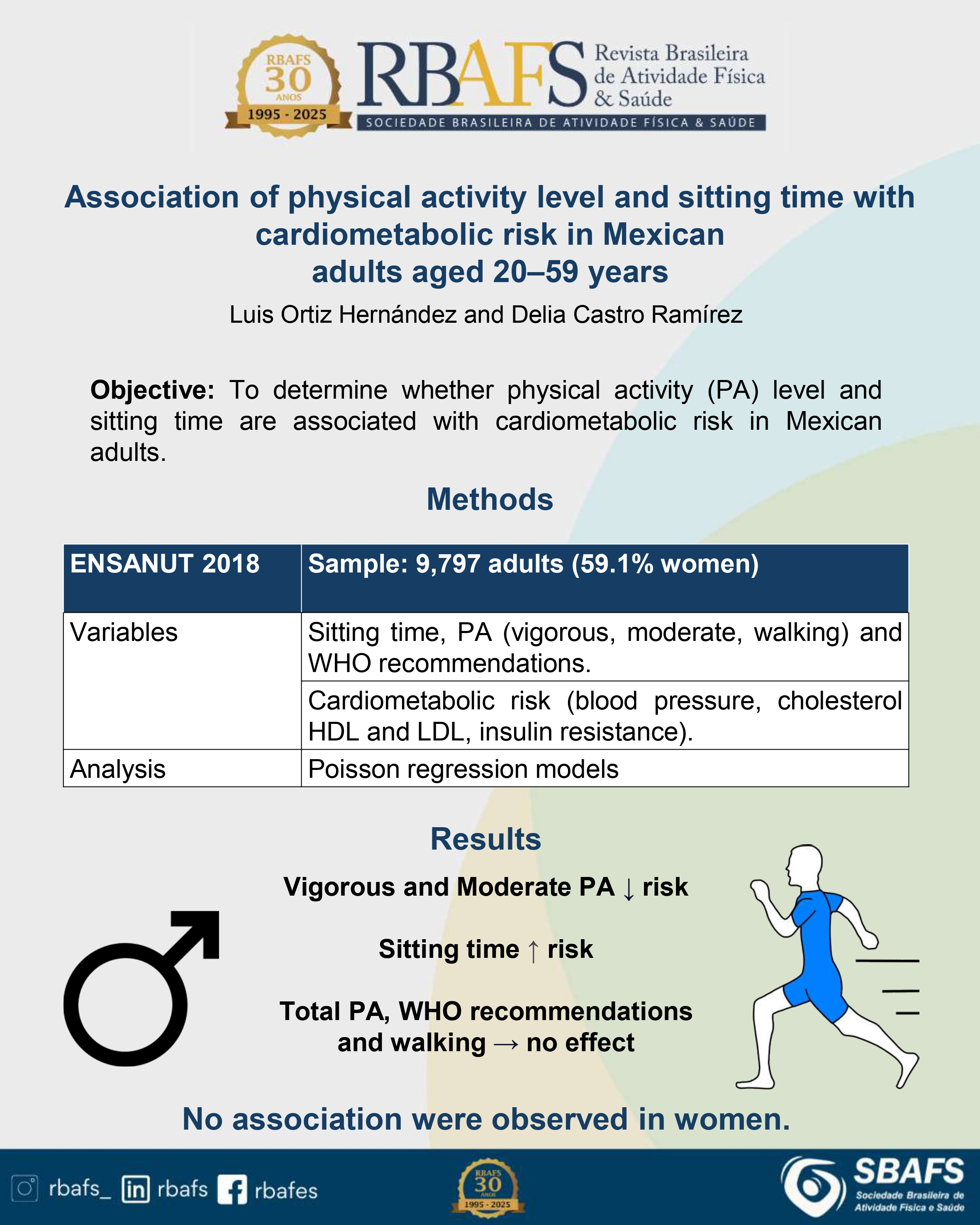

Differences by sex in the association of physical activity level and sitting time with cardiometabolic risk in Mexican adults aged 20–59 years

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.12820/rbafs.30e0413Keywords:

Body movement, Exercise, Cardiovascular risk, Sedentary behavior, Questionnaire, Vigorous activityAbstract

Introduction: There is a lack of research in middle-income countries about the relationship between physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cardiometabolic risk using representative samples. Objective: To determine whether physical activity level and sitting time are associated with cardiometabolic risk in Mexican adults. Methods: Data from the 2018 National Health and Nutrition Survey were analyzed (n = 9,797 participants, 59.1% were women). The independent variables were sitting time and five physical activity indicators: total volume (MET minutes/week), physical activity level (inactive, moderate, and vigorous), vigorous physical activity (minutes/week), moderate activity (minutes/week), compliance with the World Health Organization recommendation for physical activity, and walking time (minutes/week). Sitting time was analyzed in minutes/day. Cardiometabolic risk was assessed using measurements of blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and insulin resistance. Poisson regression models were estimated. Results: In men (but not women), physical activity level and time engaged in vigorous or moderate physical activity were associated with a lower probability of cardiometabolic risk; whereas the opposite was true for sitting time. Physical activity volume, adherence to the World Health Organization recommendation, and walking were not associated with cardiometabolic risk. Conclusion: In men, physical activity may have a protective effect on cardiometabolic risk, whereas sitting time could be a risk factor.

Downloads

References

1. Petermann F, Durán E, Labraña AM, Martínez MA, Leiva AM, Garrido-Méndez A, et al. Factores de riesgo asociados al desarrollo de hipertensión arterial en Chile. Rev Med Chil. 2017;145(8):996–1004.

2. Medina C, Jáuregui A, Hernández C, González C, Olvera AG, Blas N, Campos-Nonato I, Barquera S. Prevalencia de comportamientos del movimiento en población mexicana. Salud Publica Mex. 2023;65(supl 1):S259–S267.

3. Levy TS, Rivera-Dommarco J, Bertozzi S. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018-19: análisis de sus principales resultados. Salud Publica Mex. 2020;62(6):614-7.

4. Amirfaiz S, Shahril MR. Objectively measured physical activity, sedentary behavior, and metabolic syndrome in adults: systematic review of observational evidence. Metabolic Syndr Rel Dis. 2019;17(1):1-21.

5. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British journal of sports medicine. 2020;54(24):1451-62.

6. DiPietro L, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle SJH, Borodulin K, Bull FC, Buman MP, et al. Advancing the global physical activity agenda: recommendations for future research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. International Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):143.

7. Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, Mumford JE, Afshin A, Estep K, et al. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. BMJ. 2016; 354:i3857.

8. Rojas S, Querales M, Leonardo J, Bastardo P. Nivel de actividad física y factores de riesgo cardiovascular en una comunidad rural del municipio San Diego, Carabobo, Venezuela. Rev Venez Endocrinol Metab. 2016;14(2):117-27.

9. Andriolo V, Dietrich S, Knüppel S, Bernigau W, Boeing H. Traditional risk factors for essential hypertension: analysis of their specific combinations in the EPIC-Potsdam cohort. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1501.

10. Cao X, Zhang L, Wang X, Chen Z, Zheng C, Chen L, et al. Cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality associated with individual and combined cardiometabolic risk factors. BMC Public Health. Sep 5 2023;23(1):1725.

11. Dempsey PC, Biddle SJ, Buman MP, Chastin S, Ekelund U, Friedenreich CM, et al. New global guidelines on sedentary behaviour and health for adults: broadening the behavioural targets. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:1-12.

12. Stamatakis E, Bull FC. Putting physical activity in the ‘must-do’ list of the global agenda. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1445-6.

13. Ortiz-Hernandez L, Ramos-Ibanez N. Sociodemographic factors associated with physical activity in Mexican adults. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(7):1131-8.

14. Eastwood SV, Hemani G, Watkins SH, Scally A, Smith GD, Chaturvedi N. Ancestry, ethnicity, and race: explaining inequalities in cardiometabolic disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2024;30(6):541-551.

15. Sattelmair J, Pertman J, Ding EL, Kohl HW, 3rd, Haskell W, Lee IM. Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2011;124(7):789-95.

16. Man JJ, Beckman JA, Jaffe IZ. Sex as a Biological Variable in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2020;126(9):1297-1319.

17. Romero-Martínez M, Shamah-Levy T, Vielma-Orozco E, Heredia-Hernández O, Mojica-Cuevas J, Cuevas-Nasu L, et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018-19: metodología y perspectivas. Salud Publica Mex. 2021;61:917-23.

18. Medina C, Barquera S, Janssen I. Validity and reliability of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire among adults in Mexico. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34:21-8.

19. Committee IR. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)–short and long forms [Internet]. 2005. Disponible en: <http://www.ipaq.ki.se/scoring.pdf> [2025 Abril].

20. World Health Organization. Recomendaciones mundiales sobre actividad física para la salud. Geneva: WHO; 2010 [citado 2025 Apr 21]. Disponible en: <https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44441/9789243599977_spa.pdf> [2025 Abril].

21. Samouda H, Ruiz-Castell M, Karimi M, Bocquet V, Kuemmerle A, Chioti A, et al. Metabolically healthy and unhealthy weight statuses, health issues and related costs: Findings from the 2013–2015 European Health Examination Survey in Luxembourg. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45(2):140-51.

22. Swaleh R, McGuckin T, Myroniuk TW, Manca D, Lee K, Sharma AM, et al. Using the Edmonton Obesity Staging System in the real world: a feasibility study based on cross-sectional data. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(4):E1141-8.

23. Lopez-Hernandez D, Meaney-Martinez A, Sanchez-Hernandez OE, Rodriguez-Arellano E, Beltran-Lagunes L, Estrada-Garcia T. Diagnostic criteria for hypoalphalipoproteinemia and the threshold associated with cardiovascular protection in a Mexican Mestizo population. Med Clin (Barc). 2012;138(13):551-6.

24. Qu H-Q, Li Q, Rentfro AR, Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB. The definition of insulin resistance using HOMA-IR for Americans of Mexican descent using machine learning. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21041.

25. Levine GN, O’Gara PT, Beckman JA, Al-Khatib SM, Birtcher KK, Cigarroa JE, et al. Recent innovations, modifications, and evolution of ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines: an update for our constituencies: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(17):e879-86.

26. González M. Niveles socioeconómicos AMAI [Internet]. 2000. Disponible en: <http://www.amai.org/NSE/NivelSocioeconomicoAMAI.pdf> [2025 April].

27. Villatoro J, Medina-Mora ME, Fleiz Bautista C, Moreno López M, Oliva Robles N, Bustos Gamiño M, et al. El consumo de drogas en México: Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Adicciones, 2011. Salud Ment. 2012;35(6):447-57.

28. Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21.

29. Ahmadi MN, Clare PJ, Katzmarzyk PT, del Pozo Cruz B, Lee IM, Stamatakis E. Vigorous physical activity, incident heart disease, and cancer: how little is enough? Eur Heart J. 2022;43(46):4801-14.

30. Khurshid S, Al-Alusi MA, Churchill TW, Guseh JS, Ellinor PT. Accelerometer-derived “weekend warrior” physical activity and incident cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2023;330(3):247-52.

31. Shuval K, Leonard D, DeFina LF, Barlow CE, Berry JD, Turlington WM, et al. Physical Activity and Progression of Coronary Artery Calcification in Men and Women. JAMA Cardiol. 2024.

32. Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Jakicic JM, Troiano RP, Piercy K, Tennant B, et al. Sedentary behavior and health: update from the 2018 physical activity guidelines advisory committee. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1227-41.

33. Hwang C-L, Chen S-H, Chou C-H, Grigoriadis G, Liao T-C, Fancher IS, et al. The physiological benefits of sitting less and moving more: opportunities for future research. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;73:61-6.

Rao P, Belanger MJ, Robbins JM. Exercise, Physical Activity, and Cardiometabolic Health: Insights into the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiometabolic Diseases. Cardiol Rev. 2022;30(4):167-178

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Luis Ortiz-Hernandez, Delia Castro-Ramírez

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

When submitting a manuscript to the Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física & Saúde, the authors retain the copyright to the article and authorize the Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física & Saúde to publish the manuscript under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License and identify it as the original publication source.